The New York Times had a great piece a few days ago about the 2010 census and racial and ethnic identity.

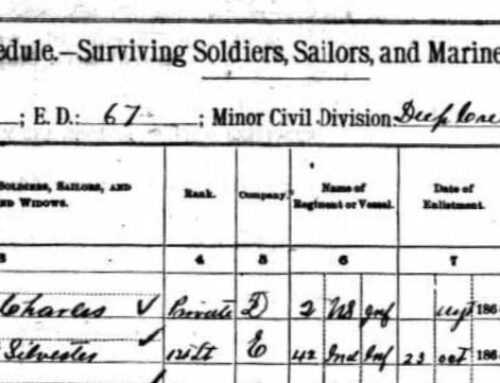

One of my husband’s lines in nineteenth-century Virginia listed as mulatto. By the time they reach Kansas a decade later, the same ancestors are white.

The Times article states:

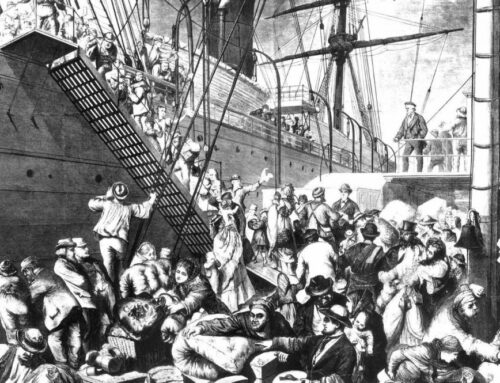

Some proportion of the country’s population has been mixed-race since the first white settlers had children with Native Americans. What has changed is how mixed-race Americans are defined and counted.

Long ago, the nation saw itself in more hues than black and white: the 1890 census included categories for racial mixtures such as quadroon (one-fourth black) and octoroon (one-eighth black). With the exception of one survey from 1850 to 1920, the census included a mulatto category, which was for people who had any perceptible trace of African blood.

But by the 1930 census, terms for mixed-race people had all disappeared, replaced by the so-called one-drop rule, an antebellum convention that held that anyone with a trace of African ancestry was only black. (Similarly, people who were “white and Indian” were generally to be counted as Indian.) It was the census enumerator who decided. [emphasis added]

By the 1970s, Americans were expected to designate themselves as members of one officially recognized racial group: black, white, American Indian, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Korean or “other,” an option used frequently by people of Hispanic origin. (The census recognizes Hispanic as an ethnicity, not a race.)

All the years I’ve used census records and it never occurred to me that the enumerator was the person who determined race. Amazing!

You can see some of the trees of people interviewed for this series here:

The Times has also added a multimedia section where you can put your own tree up:

Oh, the lengths we’ll go to to put people in “boxes.” My grandson from my side is German, Irish, French and English — but is father was born and raised in Venezuela of parents who defected from Hungary. Want a box? It’s crazy.

Thanks for reminding us.