Today I’m contemplating the combination of photo booths and family.

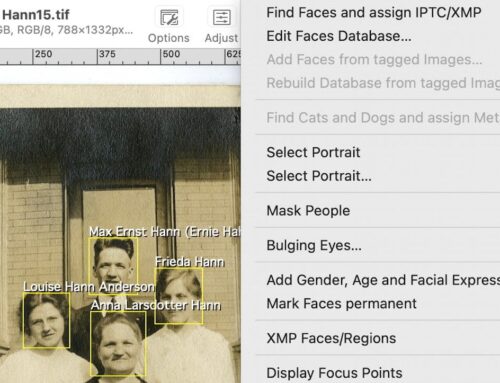

Frieda and the Photo Booth

I found this photo strip of my grandmother recently. My father’s mother, Frieda Hann, was born late in December of 1896 and raised in Chicago. To my eternal regret, I know more about her life now than I did when she was alive and available to talk to.

Although I knew who, my immediate questions about this photo strip were when and where, the cry of every family historian contemplating the blank backs of family photos.

The photo strip format itself was also a clue. Was she at an exposition or fair featuring a photo booth? The Columbian Exposition happened four years before she was born. And the Chicago World’s Fair, or Century of Progress, was in 1933 and thus too late. So, based solely on that wonderful hat and other dated photographs of her, I’d say this was taken about 1914.

Photo Booths Begin

Anatol Josepho poses in his patented invention, the Photomatron. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.)

For some reason, I thought photo booths were a far more recent invention. But the first known automatic photo machine was featured at the Universal Exposition of 1889 (Exposition Universelle de 1889) in Paris. Deposit a coin, strike a pose, and the Paris photo booth delivered a tintype, aka ferrotype (an image printed on a thin metal sheet), in about five minutes.

Seven years later in Germany, a photo booth was developed that produced both a negative and positive image.

However, online histories note that the photo booth wasn’t made commercially viable until 1925. That year, a Russian Jewish immigrant from Siberia, Anatolу Markovich Yozefovich, patented a fully automated “photographic machine.” Anatol Josepho’s process produced eight images for 25 cents. Unveiled at Broadway and 51st near Times Square, it was an instant hit.

The Curator Live site:

He crowned his invention the Photomaton, costing him $11,000 to make. People wound all the way around the [Times Square] block waiting for hours at the chance to have their likeness[es] captured.

It was Anatol who was able to produce a self-sufficient machine printing high-quality images. It was such a success that Josepho received $1 million – around $14 million in today’s money, plus future royalties for his invention.

Photo Booths Proliferate

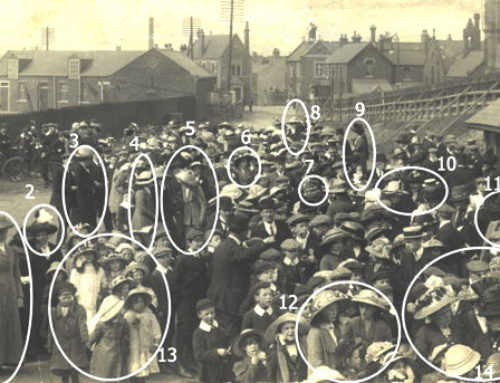

Brighton, England, photographer Abraham Dudkin, pictured with his son Lewis Stanley Dudkin, in a “Sticky Backs” photo strip produced around 1913. (Courtesy Automatic Portrait Studios).

It seems, however, that photo booths were plentiful and popular well before Mr. Josespho’s patented invention. Perhaps like all successful inventors, Mr Josepho refined and improved upon the processes of others.

In England, Spiridione Grossi, followed by Abraham Dudkin, perfected automatic photo strips known as Sticky Backs. According to the excellent website Automatic Portrait Studios, Brighton was a leading site of technological progress on photo machines. Regarding Sticky Backs, the website notes

A Stickyback Photograph is one that has adhesive matter spread on the back, which it is simply necessary to moisten and then stick the picture on the mount. ‘Stickyback’ is the name by which small gummed-photographs, not much larger than a postage-stamp, are known.” [Photo-era Magazine, Vol. 28, 1912].

Photo Booths and Family

So, given all that technological history, the question for my genealogy research remained: how common were photo booths in the mid-teens of the twentieth century?

After a few newspaper searches, I had my answer. Perhaps they were not fully automated à la Josepho, but photo booths were Midwestern staples of county fairs, church bazaars, and Lake Michigan pier-side entertainment.

About four years after my grandmother posed in that unknown photo booth, one was featured at a fundraiser at Englewood High School, located a few miles south of the Loop.

Is there anything more anodyne than a school fundraiser, especially for “some worthy war cause”? (And does it make any of my parent readers comforted to know parents 110 years ago were also raising funds for and at their children’s schools? I hope so.)

In the end, I’m glad teenaged Frieda Hann experienced the momentary excitement of a photo booth. Whether it was a place near Lake Michigan or at a church fundraiser, my grandmother looks to be enjoying herself.

As a posthumous child, my grandmother had few opportunities for fun or even outright frivolity. I have to think her strip of photo booth images was one of those times.

Leave a Reply