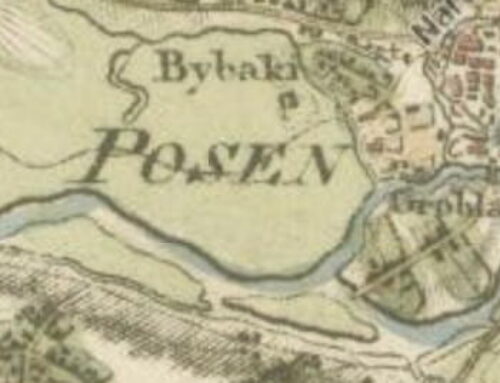

If you have research to do in North Carolina, you’ll be interested to hear about the North Carolina Maps Project, a newly completed map digitization project involving the North Carolina State Archives, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the Outer Banks History Center.

To access the North Carolina Maps Project, click here.

Archives and libraries are making the leap from digitized maps to digital maps. What’s the difference? The former is a scanned document while the latter makes it possible for users to interact, compare, and add their own data to digitized historic maps in ways that would never have been possible using only the paper originals.

The three-year collaborative project was funded by a grant from IMLS to digitize and share online images of historic maps from these three partner collections. More than 3,300 different maps, dating from 1584 to 2000, are included.

Maps are difficult records to preserve and provide access to because they are fragile yet bulky. The digitized collection provides free and streamlined access to materials, and it unifies the complementary holdings of the three partners.

“Users have responded enthusiastically from the outset, often writing to thank us for making the materials available online (and frequently asking for more),” says Nicholas Graham of North Carolina Digital Heritage Center.

In an article in March/April 2011 issue of Archival Outlook, a publication of the Society of American Archivists, Graham writes:

In order to move from digitized maps to digital maps in the North Carolina Maps Project, a couple steps were necessary.

First, we had to georeference selected historic maps and devise ways to present them online. Georeferencing is a familiar process for GIS specialists. It involves assigning a digital image and assigning it a place in physical space. For our project, this usually involved comparing a historic map to existing, known geographic information, such as a layer of streets or a satellite image. The person conducting the georeferencing finds a spot on the historic map that matches a corresponding spot in the known geographic layer, such as a road or railroad intersection. The software then aligns the historic map to the existing digital information. The more points found on the historic map, the more accurate the results.

Of the more than 3,000 maps available on the North Carolina Maps Project website, about 200 are presented as georeferenced, or “historic overlay,” maps. There’s no easy or automatic way to georeference a map. It can take many hours to complete even one. Once a historic map is georeferenced, it can be used like any other geographic layer.

What the georeferencing means for users of the new North Carolina Maps Project is the ability to view a historic map directly on top of a current map or satellite photo, generating a comparison of the same area past and present. Changing roads and borders, seeing the location of specific buildings, another command are possible.

Similar projects combining user-friendly GIS applications offered by Google with collections at the University of Connecticut and Ball State University are underway.

Leave a Reply