Research on Free and Enslaved African American Lives Continues

New understanding of the lives of those enslaved in the early 19th century at Montpelier–the estate of James Madison, 4th president of the United States–continues to evolve. And new insight into Easton, the first free Black community on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, is also coming to light.

New Attention to Lives of Montpelier Enslaved Americans

First is an updated article, “Understanding This Lost Plantation,” in the Culpeper Star-Exponent on James Madison’s estate, Montpelier. An 1837 insurance plat helped archaeologists identify a dozen sites where field, house, and skilled artisan enslaved people once lived. At his death, Madison – Father of the Constitution and architect of the Bill of Rights – owned 108 slaves, who were sold and separated by his widow, Dolley Madison,

The newspaper article notes:

What remains ‘invisible’ today at Madison’s home is the plantation itself – the homes of the enslaved work force, the network of fields, the work areas, and the roads that characterized this Virginia plantation,” Reeves said in his paper. “The first step in understanding this lost plantation landscape is conducting in-depth research on the enslaved community that called Montpelier home.”

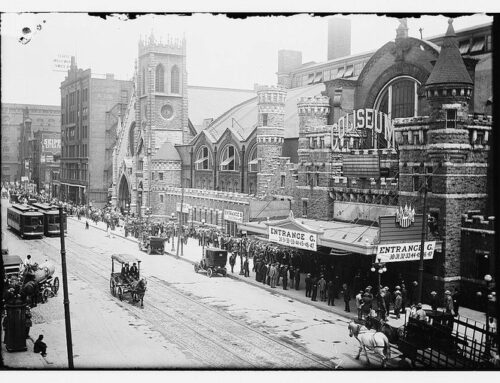

Timber frames mark the footprint of enslaved community housing at Montpelier.

Montpelier Archeology

To more accurately understand the lives of enslaved people at Montpelier, archaeologists there acquired a new tool called LiDAR (light detection and ranging). This technology permits archeologists to

uncover subtle terrain changes on that are present on the ground surface but invisible to the naked eye. It is essentially like acquiring x-ray vision so we can see features such as historic roads, field edges, and even plow furrows. Over the past thirty years, archaeologists have found hundreds of sites across the property such as [enslaved] quarters, barns, and work sites; now we can connect these historic sites with the location of fields, historic paths and road traces. This allows us to literally walk in the foot steps of the enslaved across the landscape.

At a 2011 ceremony in the basement of the mansion where enslaved persons once worked, descendants of those born into bondage at Montpelier honored their ancestors. Judge John Charles Thomas of Richmond, the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court of Virginia, offered insightful remarks. He said:

We have to remember that though we speak today in terms of archeology and science, digital reconstructions, shovel test pits and electromagnetic conduction to see if we can find a fragment or a bone, we are talking about the lives of people.

Discovering Free African Americans in Easton, Maryland

More research comes to us from Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where archeologists and researchers are uncovering the story of Easton, a community of free African Americans at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Piece by piece, archaeologists and historians from two universities and the local community are uncovering the history of The Hill, a part of the town of Easton believed to be the earliest community of free blacks in the United States, dating to 1790.

It may also have been the largest community of free blacks in the Chesapeake region. During the first census in 1790, about 410 free African Americans were recorded living on The Hill — more than Baltimore’s 250 free African Americans and even more than the 346 slaves who lived at nearby Wye House Plantation, where abolitionist Frederick Douglass was enslaved as a child.

Morgan State University archaeologist Dale Green, leading a tour in this photo, is a key figure in The Hill Community Project, researching the lives of free Black Americans. (courtesy secretsoftheeasternshore.com)

Further research points to Easton being the earliest free Black community in the country. Morgan State University archaeologist Dale Green is researching and leading tours of The Hill neighborhood in Easton.

For many years, historians gave the title of oldest black community in the country to a neighborhood in New Orleans called Tremé, which dates its African American story back to 1812. But thanks to an extraordinary research and revitalization project in Talbot County, Maryland, it’s now apparent that a neighborhood on the Eastern Shore has Tremé beat by more than two decades.

Continuing Research on Free and Enslaved African American Lives

New research and new technology continues to reveal more about free and enslaved African American lives. And yet as Judge John Charles Thomas said:

I don’t think we ever have to dig into the ground to understand the pain of not being free.

For more posts about African American genealogy research, click here.

Leave a Reply